In 2012, Dr. Alan Johnson sketched out a number of new and promising concepts for medical devices. At the time, he was only a few days into the Medical Devices Center’s Innovation Fellows Program, based in the University of Minnesota’s Medical Devices Center.

But as Johnson learned more about what it takes to turn a lab invention into a commercial product, he started to see technological, financial, and regulatory hurdles looming. One by one, he crossed ideas off the list. At the end, one promising invention remained: a new, noninvasive method for safely and securely closing the jaw to help it heal after a fracture.

Now, five years later, Johnson’s invention has become the first technology born in the Innovation Fellows Program to finish navigating the complex path from lab to marketplace. Following a licensing deal with St. Paul-based Summit Medical, Inc. and the recent receipt of U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearance, the device can now be marketed for use in surgeon’s offices, hospitals, and clinics across the country.

Johnson, who now works as a head and neck surgeon in Grand Forks, N.D., has a long history with the U of M. Apart from his involvement in the Innovation Fellows Program, he spent four years at the U’s Medical School and five more as an otolaryngology resident there.

Jaw fractures most commonly result from blunt force trauma, such as vehicle crashes, sports injuries, and physical assault. Keeping a fractured jaw closed helps it heal properly, but the conventional metal wiring method of doing so presents a few problems. For the patient, a wired jaw is uncomfortable, can lead to irritation on the lips and gums, and can even contribute to gingivitis. For surgeons, the sharp tips of the wires are a safety hazard. One poke creates the risk for disease transmission.

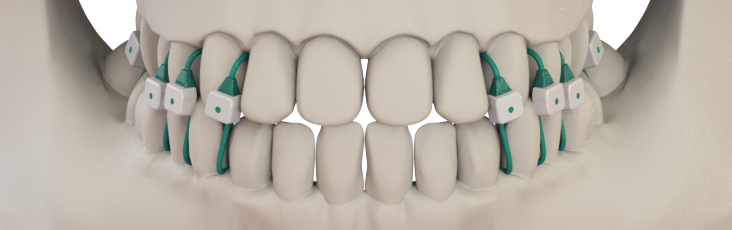

Johnson’s invention is a set of smooth, blunt-tipped sutures inserted between the teeth that securely close the jaw with less discomfort than metal wires and fewer dental hygiene problems. A surgeon can apply these sutures more quickly and safely than wires, and may even be able to put the device on a patient in a clinic setting to reduce the costs and delays of scheduling an operating room visit. Keeping safety a priority and costs down could be good not just for patients and surgeons, but for hospitals and insurance companies as well.

“We hope that this can decrease the cost of care by eliminating some operating room trips,” Johnson said. “That’s really why this technology has worked; all of the key stakeholders all win.”

Woodshedding an Idea

The Innovation Fellows Program caught Johnson’s interest when it was created in 2008. He was still in the middle of his residency then, but spent a lot of time with the first year’s fellows to learn more about what they were doing. When he later joined the program, he found it to be an immersive experience.

“The fellowship was extremely engaging, a very exciting, challenging, and humbling experience,” Johnson said. “You get exposed to all sorts of things, not just those in your particular field.”

Arthur Erdman, Ph.D., director of the U’s Medical Devices Center and mechanical engineering professor in the College of Science and Engineering, said Johnson’s work as a fellow included finding out whether his approach to treating jaw fractures was sufficiently different from any existing, patented technologies. He also had to ensure it would fit the differing teeth and gums of different people.

“When Alan started to explore the original idea, the potential medical impact was apparent to me based on my many past dental-related R&D projects,” Erdman said. “The concept was simple and elegant, but he still faced significant engineering and manufacturing challenges.”

The program helped Johnson overcome these obstacles. He had the opportunity to test his prototypes extensively and to gather lots of feedback from the University research community and medical device professionals. Johnson also worked closely with co-inventors Laura-Lee Brown and Christopher Rolfes, both MDC fellows, and Samuel Levine, M.D., professor in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery.

Partnering to Reach the Market

Erdman said Johnson and his collaborators’ ample testing and prototyping of the technology helped them reach the point where industry partners would be more interested in adopting the technology through a licensing agreement.

“Alan took full advantage of the prototyping facilities at MDC,” Erdman recalled. “It seemed that each time I looked at the mechanical fabrication lab across from my office, I would see Alan busy making improvements on earlier prototypes. The numerous design-build-test cycles brought the project to a point where Summit Medical could evaluate the finished proof-of-concept.”

On the licensing side, Johnson worked closely with Karen Kaehler and Kevin Anderson in the U’s Office for Technology Commercialization to patent the technology and, ultimately, to negotiate the license deal with Summit Medical.

Once Summit Medical licensed the technology, Johnson began to visit the company every six to eight weeks to advise on many aspects of research and development. He assisted with instruction materials, bench testing, FDA clearance requirements, and feedback on design of the product itself.

Ultimately, this collaboration resulted in Minne Ties Agile MMF. With FDA clearance, the device can now be used to treat jaw fractures in a safer, more comfortable way.

“I hope that it’s adopted in a widespread fashion, and that patients and physicians feel that it’s better than what we’ve had before,” Johnson said.