Earlier this month, a team of experts from the University of Minnesota demonstrated to industry peers how innovative approaches in spatial research can provide new perspectives on the world around us and prepare us for the way society is evolving.

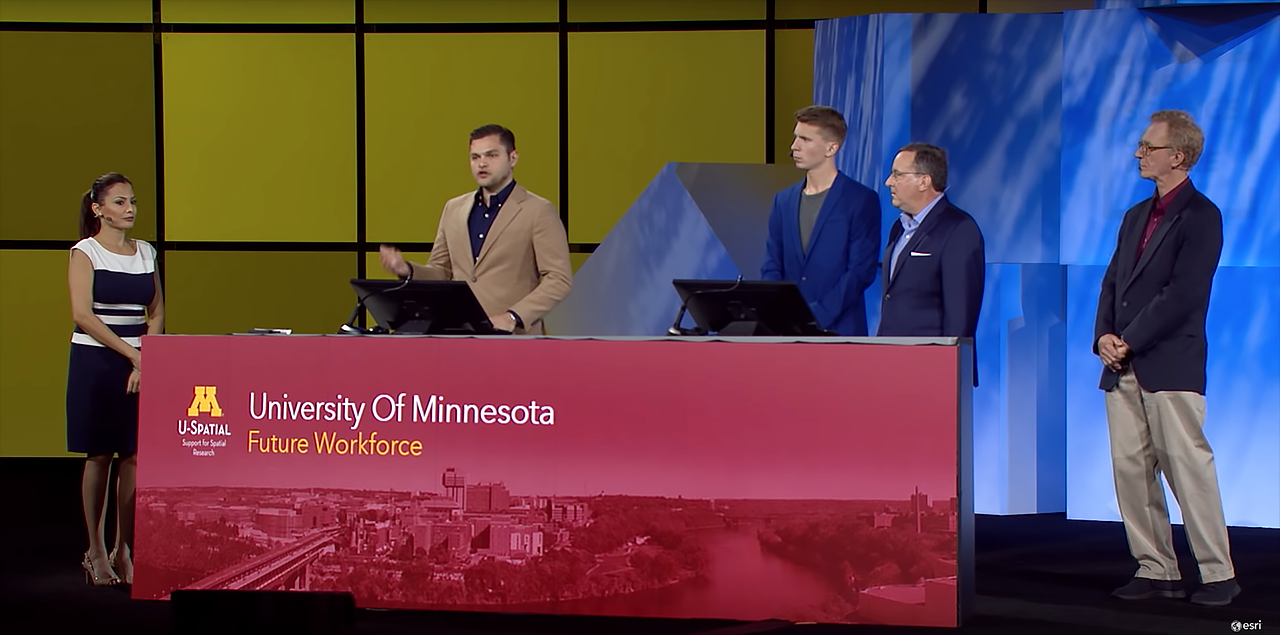

The team spoke in a July 9 plenary session at the 2018 Esri User Conference, an international gathering of mapping and geographic information systems (GIS) experts. Their presentation, “Advancing Spatial Science and the Workforce of Tomorrow,” highlighted spatially driven education, research, and community outreach efforts that are helping U researchers solve complex challenges and create a spatially aware and connected future workforce.

The University became one of the world’s first “spatial universities” at a time when public and private sector interest in spatial thinking and approaches was starting to rapidly increase. At the heart of its spatial capabilities is U-Spatial, which serves and drives a fast-growing need for expertise in GIS, remote sensing, and spatial computing. U-Spatial is nationally recognized as a leading model for how universities can successfully integrate spatial data, visualization, analysis, and spatial thinking.

“Our charge at U-Spatial is to develop the GIS workforce of tomorrow,” Len Kne, associate director of U-Spatial, told Esri User Conference attendees. “To ensure that everyone in the workforce is thinking spatially, and to advance the geospatial sciences.”

U-Spatial supports thousands of faculty, staff, and student researchers across campus. In the last 12 months, more than 20,000 maps have been created to show campus sidewalk conditions, farming practices, mapping the premodern world, digital elevation models of ice shelf elevation in Antarctica, and much more.

Spatial Research in Action

Telling the Story of Volcanic Activity

Coleman Shepard, a master of geographic information science student and a research assistant with U-Spatial, described to conference attendees one of his most recent projects—tracking the recent eruption of Kilauea, one of the youngest and most active volcanoes on the Hawaiian Islands.

“One thing I’m learning is how to leverage spatial thinking to tackle real-world problems,” Shepard said. “I wanted to use spatial technologies to further explore the dynamics of the recent lava flows.”

Using satellite imagery, Shepard was able to clearly track lava flows over the landscape around Kilauea over time. Delving deeper, he was able to map three distinct clusters of earthquakes associated with the eruption and their effect on the stability of the surrounding regions, including how land was displaced and caused changes in elevation.

Ultimately, Shepard created a map that visually communicated the story of the eruption.

Bringing Structural Racism to Light

Racial restrictions in property deeds, called racial covenants, were used in most US cities before 1968 to prevent nonwhite people from buying or occupying property in some areas.

Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, a Ph.D. student of geography, environment, and society in the College of Liberal Arts, is part of an effort to plot racial covenants in Minneapolis and the rest of Hennepin County to create the first-ever comprehensive map of these previously invisible discriminatory deeds.

“Often just a few lines of text, these restrictions were embedded in warranty deeds throughout the United States,” said Ehrman-Solberg, who serves as digital and geospatial director with the Mapping Prejudice project. “And while we are still a work in progress, our preliminary results are already shedding new light on how structural racism was embedded into the very built environment of Minneapolis.”

Local city planners will use the map to redesign municipal zoning codes, he said, while government officials are using it to reframe long-term planning and development through an equity lens.

“GIS is not only a powerful tool for analysis, but can be an equally powerful tool for social justice,” Ehrman-Solberg said.

Understanding How Animals Move

Somayeh Dodge, Ph.D., assistant professor of geography, environment, and society with the College of Liberal Arts, described how spatial research can push beyond mapping locations to map the motion of living beings.

“My research focuses on understanding and predicting movement through analytics and visualization,” Dodge said. “Using movement data, we can learn a great deal about the behavior of individuals, and from that, predict change in natural and human systems.”

For one example, Dodge tracked the movement of an albatross from its nest in the Galápagos Islands to Peru, where it foraged for food. She examined how the bird’s path was determined by where food was abundant, and how it waited for a favorable tail wind before beginning the two-week flight to the Galápagos.

In another project, she tracked the movements of two tigers, studying the way they patrolled their territory and interacted with one another. Her spatial approach made it possible to track the tigers’ movement not only across time and space, but in the context of the environment as well—showing, for example, that the tigers avoided traveling across hilltops.

What’s Next?

Where will spatial research take us next? Tom Fisher, director of the U’s Minnesota Design Center, said technological advances are opening up opportunities for humans to return, in some ways, to their nomadic roots.

With the rise in digital tools that allow us to pay for and use only what we need, Fisher said, we are returning to a time when owning possessions is no longer as necessary. “Ridesharing” companies like Lyft and Uber are making it possible to travel by car without buying a vehicle, while car companies themselves are developing driverless vehicles that no individual would own. Airbnb, meanwhile, has become the world’s largest hotelier without owning a single room.

“These companies embody this new nomadic mindset: owning very little and accessing a lot,” Fisher said. “They are part of a larger sharing economy that is squeezing out the inefficiencies of the 20th century, where we overproduced goods and overconsumed resources in unsustainable ways.”

Spatial thinking will be essential to this new economy, he said. Mapping opportunities and making connections that were previously unseen will help spatial experts examine the impact of new technologies and play a role leading the transition.

Advancing Spatial Science & the Workforce of Tomorrow

Watch the U of M’s full presentation at the 2018 Esri User Conference:

Learn more about U of M spatial research capabilities.