Latest estimates show that 6.5 million Americans are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease. This number is predicted to double by 2050. There’s currently no cure, in part because doctors cannot diagnose the disease until it is symptomatic and advanced.

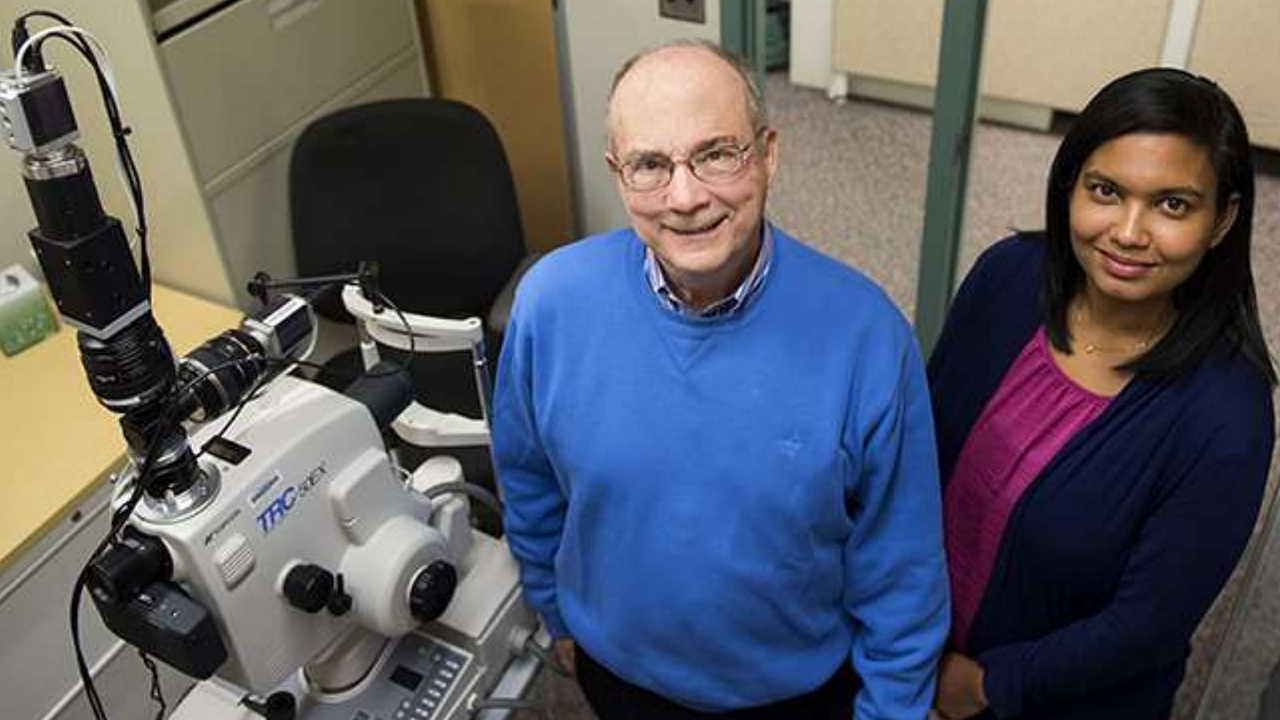

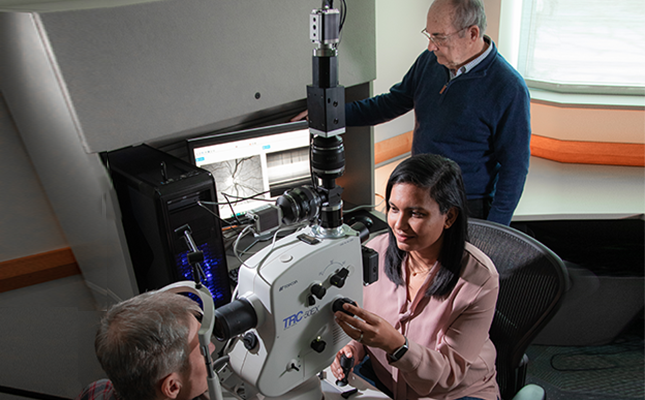

Thanks to the research of Robert Vince, PhD, director of the Center for Drug Design (CDD) in the University of Minnesota's College of Pharmacy, and Swati More, PhD, associate professor, CDD, we now have a noninvasive tool for earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease through the retina. Clinical studies have demonstrated the retinal scan’s ability to safely and accurately detect brain changes.

OVPR is proud to recognize this incredible and important work by granting Vince and More the inaugural Innovation Impact Case Award, which highlights research that has had a significant impact outside of academia and made a meaningful difference in our communities. Included with this recognition is a $10,000 cash prize.

An Intriguing Journey: From Compound to Camera

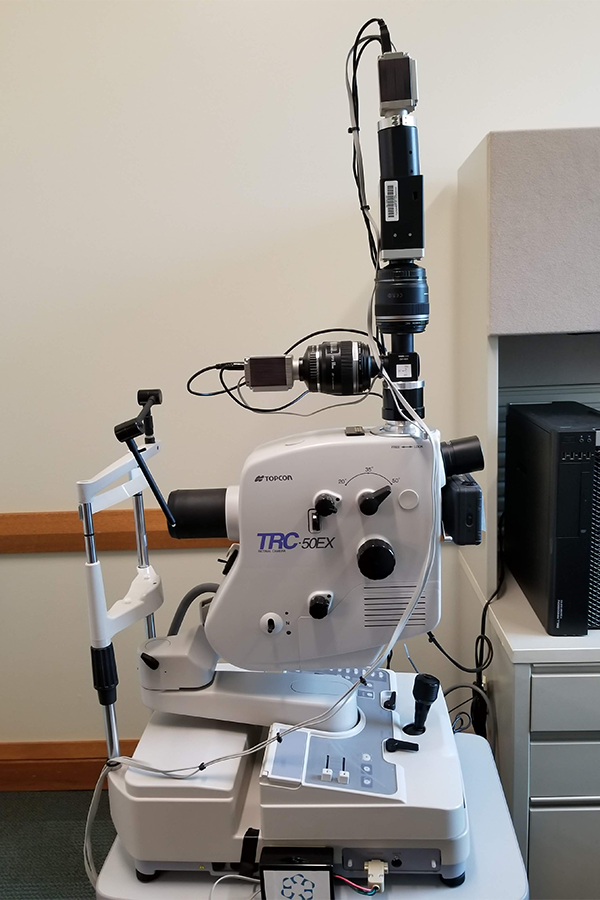

As always, inventions are born out of need. While developing compounds to treat early Alzheimer’s, More and Vince were faced with an urgent need for a much faster way to test the efficacy of potential drug candidates. They began using a specialized hyperspectral imaging microscope to monitor the development of amyloid plaques, the tell-tale sign of Alzheimer’s, in brain cells and to see a potential compound’s impact when they came up with a new hypothesis.

“The eye is an extension of the brain,” said Vince. “If we can see these plaques develop in the brain, maybe we can also see it in the eye.”

They first tested this theory on mice and were able to confirm the retinas mirrored the plaque-development process they’d seen in the brain. The next step was to create a scanning technology. They collaborated with biomedical engineer Jim Beach, PhD, an adjunct research professor in the CDD, and successfully developed a camera for mice followed by a camera for humans.

Earlier Detection of Alzheimer’s

PET scans are currently the gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s. However, plaques have to be present before the PET scan will spot them, and according to Vince and More, the plaques aren’t the real problem.

“The plaques are the after effect,” Vince explained. “It’s like if you took a log and burned it. The fire is what destroyed the log, the pile of ashes are what’s leftover. The plaques are like ashes.”

While the PET scans identify the ashes, More and Vince’s technology has the potential to detect the fire. “Our technology focuses on what happens before the plaques form. We think it could detect changes during the earlier stages of the disease,” More said, adding that the noninvasive process is a fraction of the cost of a PET scan, radiation-free, and takes only minutes to complete. “We envision this scan as part of an annual eye exam and a tool for doctors to monitor changes in their patients.”

What’s Next?

In their lab, More and Vince continue to use their technology in Alzheimer’s research and plan to look at other conditions, including Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Their scanning technology will help them and other researchers with more efficient drug development and testing.

“Developing a drug from discovery to approval costs about $1.5 billion,” Vince explained. “This scanner can help ensure the compounds are working before too much money is invested.”

About the Researchers

Robert Vince has been at the University since 1967. When he started, he was the youngest professor on campus and taught at the College of Pharmacy. During this time he developed Ziagen, a drug used to treat AIDS, and earned the University $600 million in royalties that were reinvested in graduate student support and other academic purposes. Vince used a portion of the royalties to start the Center for Drug Design, which he has directed since.

Originally from India, Swati More moved to Minnesota in 2002 and joined the Vince lab, where her thesis formed the basis of their Alzheimer’s research. After earning her PhD in medicinal chemistry, she completed postdoctoral work at the University of California, San Francisco, where she studied pharmacogenomics of anticancer drugs. After returning to the University, she resumed Alzheimer's research in collaboration with Professor Vince.