In the past, people looked to barometers to forecast the weather. A low pressure reading meant wind and rain were likely, but it was only an educated guess. Soon after World War II, meteorologists successfully began using Doppler radar, which allowed them to track an actual storm and map its progress.

In 2000, University of Minnesota cardiologist Dr. Jay Cohn developed the Doppler of heart disease. His Rasmussen Disease Score is the first method of determining whether a patient suffers from cardiovascular disease long before he or she feels symptoms or suffers a heart attack. And now, thanks to collaboration with local company CVC HeartSavers’ efforts to expand the reach beyond campus, more and more people are able to see the turbulence in their own health and take precautions before a medical storm hits.

Cohn, director of the U’s Rasmussen Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention, developed the method as a way to actually detect heart disease, not just react to risk factors, which can be misleading or absent altogether.

“The risk factors used in the past can be inadequate guides in determining who should take a cholesterol-lowering drug, for example,” Cohn said, adding half of those in the early stages of heart disease have normal blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

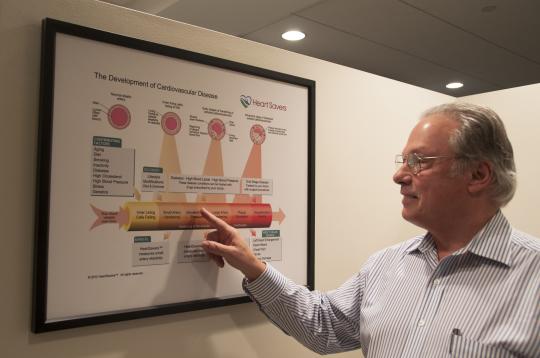

Cohn’s method includes a series of 10 tests that numerically evaluate artery and heart health to measure whether heart disease is present and, if so, how severe it is. A score of six or higher on these tests means the patient likely has plaque build-up in the arteries, or atherosclerosis, while a score of three to five suggests that such a problem may be developing. A score of two or less signals a patient is fine but should return in the future for another test. The method detects disease at the earliest moment, before the traditionally used calcium score would show any signs of trouble. In recent years, Cohn has created a simple four-test screen that is used to identify individuals in need of the full evaluation.

Until recently, however, the test was limited to the university and referrals from the University of Minnesota Medical Center. Cohn and the U’s Office for Technology Commercialization set out to change that. Soon Maury Taylor, who had worked with the U in pharmaceutical development for many years and has a background in chronic diseases, developed the plan to expand the companies CardioVascular Centers and Hypertension Diagnostics, which were started by Cohn and his partners Ron Dropik, who developed the information technology systems; and Dr. Paul Sommers, who previously worked at the U with Cohn himself. The two related companies are expanding the test’s application and continuing production of the CV Profilor device used to perform it. Taylor, who came on board to commercialize the concept, leads the companies as executive director.

CVC HeartSavers opened for appointments in the downtown Minneapolis BakerCenter skyway in February 2013, expanding Cohn’s heart disease detection to a larger audience. The clinic takes appointments, referrals and walk-ins. HeartSavers can perform about 30 “Cardio 101″ tests a day, each of which takes about 20 minutes and is painless, non-invasive and radiation-free. If clinicians diagnose someone as having heart disease, that patient returns for a Cardio 1000 test, where more detailed tests collect data. A proprietary algorithm processes the information and informs development of a personalized treatment plan to stop heart disease from advancing and to promote recovery.

“The panel of tests is designed to be very discriminating, which produces the best evidence-based personalized treatment plan,” Taylor said. “This plan is a clinical decision support system, which, when administered by a primary care physician, can yield the best outcomes for an individual.”

While HeartSavers does serve patients in the local community, Taylor said the storefront has a second role: to serve as a commercial demonstration site for upcoming locations. Before other clinics and entrepreneurs decide to adopt the test for use in their area, they can visit HeartSavers to see how it works in a clinical setting.

“We have people coming in here from all over the world who are interested in what we’re doing,” he said, adding that visitors from as far as Iceland and the Middle East visit to understand how the assessment works, examine the equipment and, of course, undergo the test. “They say, ‘Well, show me what you do – on me.’”

Sites in Florida, Louisiana and Georgia are also now running the tests under an agreement with CVC HeartSavers. Closer to home, Taylor hopes to serve all of Minnesota, which could mean three to five additional locations spread out over the state. There will also be referral facilities connected to primary care providers, so trained staff can administer the test in the same places where patients get regular checkups. One such facility was recently established at Life Medical Clinic in St. Louis Park.

“We make it easy for the patients,” Taylor said. “We actually set up a Cardio 101 program in their clinic.”

Cohn and Taylor aren’t the only ones pushing to reduce heart-related health problems. Their efforts align with a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiative to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017. About 600,000 people die of heart disease every year in the U.S., and coronary heart disease alone costs the country $108.9 billion each year, according to the CDC website.

As for Cohn, he’s excited to see the Rasmussen Disease Score expanding further into public reach, where it can benefit a greater number of patients. Too few people who suffer heart attacks are taking the medications that could have prevented them, he said.

“This has been my mission for the last 13 years, to bring this methodology into the mainstream,” Cohn said. “I feel very strongly there is room for major advances in reducing the risk of heart attack and strokes.”

Originally published on Business @ the U of M.