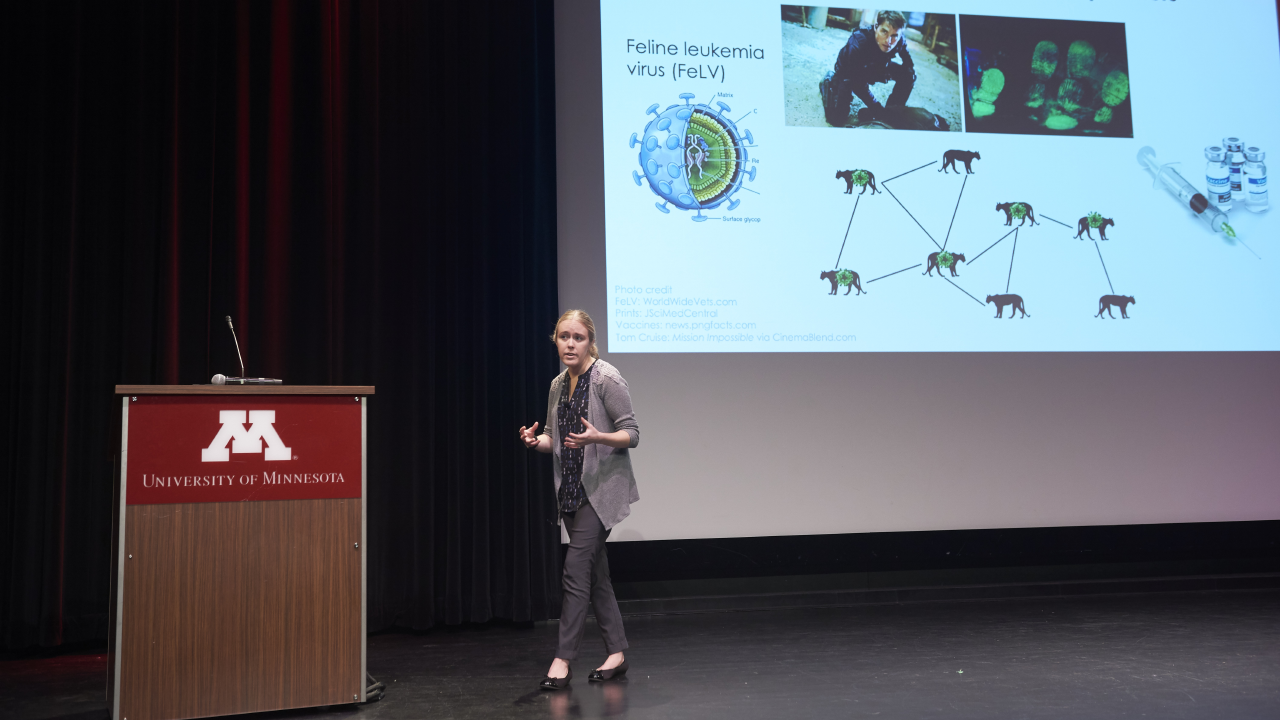

Marie Gilbertson, PhD student in the College of Veterinary Medicine, presents her research into the spread of feline leukemia virus on November 8 as part of the University-wide Three Minute Thesis competition.

When Marie Gilbertson took the stage at the University of Minnesota earlier this month to explain her research into a deadly virus threatening mountain lions, she wasn’t speaking to a conference full of veterinary experts, nor to fellow College of Veterinary Medicine doctoral students. She was talking to everyone else.

Gilbertson was competing in the fourth annual University-wide Three-Minute Thesis (3MT) competition, where students have just three minutes and one presentation slide to summarize their research. The event, hosted by the Graduate School and based on the 3MT created by Australia’s University of Queensland that is now held at over 600 institutions worldwide, is about more than friendly competition. It teaches a key skill for researchers: speaking about their work in a concise, meaningful way to people outside of their field.

“As scientists, we really love to emphasize the how part of our work, but tend to forget to talk about the why,” said Gilbertson, who took first place in the competition. “And unfortunately, the how part is generally the most jargon-heavy and difficult to understand for nonscientific audiences.”

Scott Lanyon, PhD, the U’s vice provost and dean of the Graduate School, said learning to assess an audience and present highly specialized research in a way that resonates with them is a crucial skill for a student’s academic and professional career. The 3MT competition and the thematically similar Speaking Science conference are two ways graduate students can learn to do this.

“It doesn’t matter what your career path is, you need to be able to communicate complex ideas,” he said. “Asking researchers to communicate what they’re doing to a nontechnical audience forces them to do that self-reflection of, ‘why might somebody care about what I do?’”

There are many benefits researchers can reap from good communications skills, including showing a faculty search committee that they can teach nuanced concepts to undergraduates, explaining to legislators the potential societal impact of a line of research, opening doors to collaboration with researchers in other disciplines, or convincing funding organizations that a research project deserves investment.

Whittling it Down, Telling a Story

Over the course of her graduate schooling, Gilbertson found science communication has become an increasingly important skill for her, whether she was applying for research fellowships, meeting with legislators, interacting with donors, teaching students, writing manuscripts, presenting at conferences, or being interviewed by journalists.

“In all these spheres, I’ve had to consider how to structure my message to have the greatest impact, given the audience and communication medium at hand,” Gilbertson said. “Effective communication is therefore a part of my daily life as a scientist, and the 3MT competition was an important way for me to further grow and expand my skills in this area.”

Gilbertson’s thesis focuses on how to better predict and prevent outbreaks of the deadly feline leukemia virus in an endangered subspecies of mountain lion called the Florida panther. As she worked to condense it into three minutes, Gilbertson made sure to avoid using terms like “mathematical modeling” and “genomics” and sought instead to take a broader view of the subject that highlighted its importance.

When it comes to changing an audience’s attitudes or inspiring action, it can be tempting to focus on supplying more information, Gilbertson said, but a well-told story can be much more potent.

“I think, with stories, we are able to convey emotions and ideas that break down barriers and open people to more personal connection,” she said. “Those connections are what change hearts, minds, and behaviors.”

Going forward, Gilbertson hopes to continue in academia, working on complex issues in human, animal, and environmental health, where effective communication will help her collaborate across disciplines and stakeholders.

A Shift in Graduate Education

Greater attention to being able to communicate about research is one piece of a larger shift in how the University thinks about graduate education. Traditionally, grad school has focused on two elements, Lanyon said: curriculum (learning the core knowledge of a discipline) and research (where students cultivate a more specialized understanding of the field). Increasingly, however, it’s becoming clear that there are more generalized skills that live outside of any individual discipline that will help students succeed in their academic and professional careers.

That’s why the Graduate School recently introduced digital badging, a series of “micro-credentials” that students can earn by completing optional workshops and trainings. These opportunities aim to help students brush up on practical, relevant skills in areas like public speaking, cross-cultural communication, and leadership. Before the end of this year, the Graduate School will launch GEAR+, a collection of online resources to develop such skills.

Students who complete them can place badges on their digital CVs, cover letters, or personal websites to show they have these skills. Clicking the badge leads to a secure, verified site that shows details about the content of the workshop and the experience it provided. Students who want to go into nonprofit management, for example, might take workshops that teach how to manage a budget and supervise employees.

“Our graduate students are going after ever more diverse career paths,” Lanyon said. “The more of these skills they pick up, the more successful they will be.”

Share Your Research (and Help Others Share Theirs)

Attention graduate students: The Graduate School is collecting your ideas for sharing research into a single website to create a resource for how to best communicate with a general audience.

Submit a tip to help your fellow student researchers communicate their work more effectively or add your research as an example to inspire others.