Many times, new ways of thinking and viewing our world stem not from deliberate planning, but from happy accidents, sparked from a chance meeting or an unexpected question.

The University of Minnesota’s Office of the Vice President for Research is exploring how serendipity can grant new perspectives and lead to new discoveries and breakthrough research. Through its strategic plan, Five Years Forward, a work group made up of faculty from across the U is looking at ways to create new spaces, tools and opportunities for researchers to come together across departments, colleges and disciplines to think creatively and cultivate new ideas. One of these faculty members, Department of Plant Biology professor Neil Olszewski, Ph.D., can attest to the value of serendipitous collaboration from prior experience.

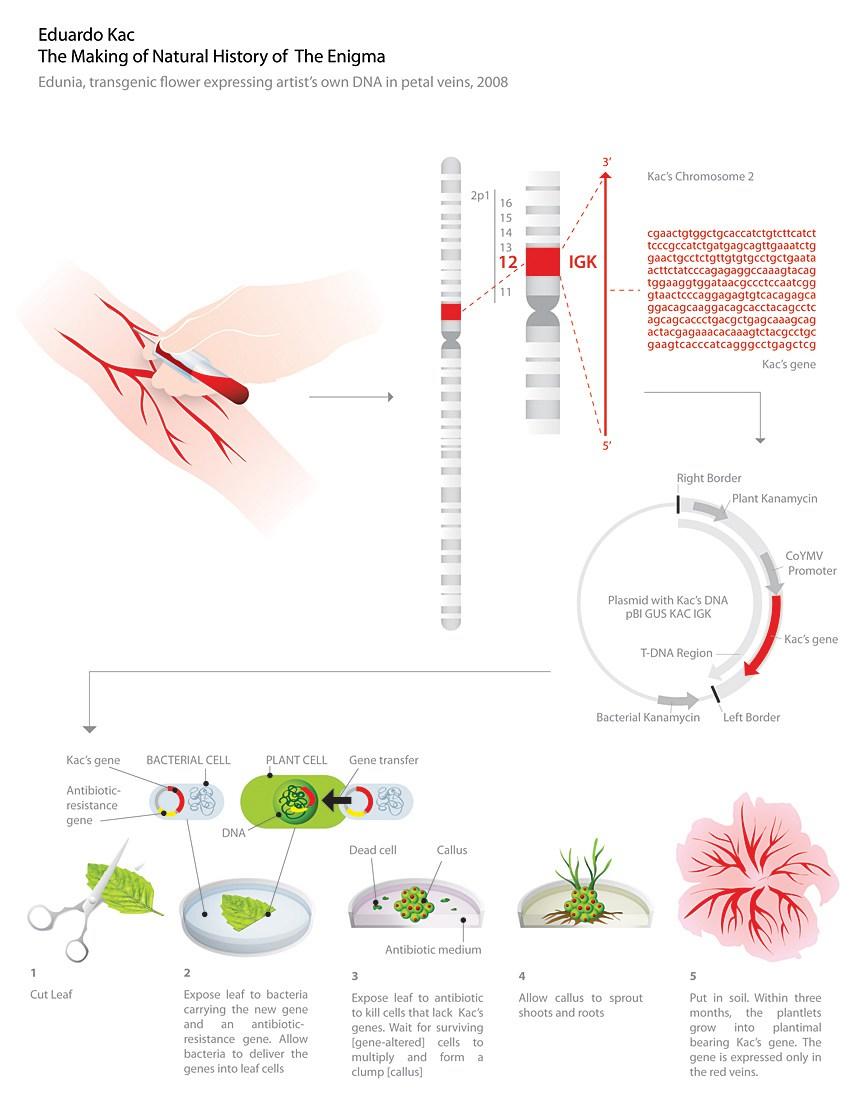

From 2003 to 2008, Olszewski worked with Eduardo Kac, internationally recognized artist and professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, on a project to create a transgenic flower — one that incorporated genes from another organism (in this case human genes). Their efforts brought together art and plant biology in an unprecedented way.

“You get around bright people who think about the world differently than you do and it gets you thinking about things differently,” Olszewski said. “There’s a real benefit in working across disciplines like this.”

Olszewski and Kac’s collaboration came about by chance. In 2003, Kac had been commissioned to create a sculpture in front of the newly constructed Cargill Building on the U’s St. Paul campus. Kac invited faculty to meet with him and discuss a genetics-themed idea he had not only for the sculpture, but for a related exhibit. The invitation piqued Olszewski’s interest.

“Kac’s work really resonated with me,” Olszewski said. “I liked the way he explored philosophical ideas through art and science.”

Kac set out to create a transgenic flower that would get people to consider the commonalities between plants and animals. He had a sample of his own blood drawn and a genetic sequence isolated from an antibody within it. Then he brought the antibody DNA to Olszewski, who spliced Kac’s DNA in with a petunia and began growing the transgenic “plantimal.” Due to the presence of a genetic promoter identified by Olszewski’s lab in the petunia’s transgene, Kac’s protein was expressed in the red veins of the flower’s bright, pink petals. The resulting effect was both striking and symbolic.

“It uses the redness of blood and the redness of the plant’s veins as a marker of our shared heritage in the wider spectrum of life,” Kac said.

The plant, which Kac named “Edunia,” has a completely unique genetic makeup and is not found anywhere else in nature. It became the living centerpiece to an exhibit at the U’s Weisman Art Museum in 2009, where visitors were able to observe it up close and consider what it means for a plant to carry human DNA. Named “Natural History of the Enigma,” the project provided a visual commentary on the contiguity of life between different species.

Conversations Across Disciplines

During their collaboration, the two had numerous discussions that allowed them to explore the concepts at play and approach them from creative angles. Kac had a strong interest in understanding the science behind modifying the molecular biology of the plant and understanding what outcome they predicted it would have.

“To work with Dr. Olszewski was a remarkable and memorable experience,” Kac said. “The production of the artwork was challenging and to have succeeded six years later was indeed rewarding.”

Meanwhile, Olszewski experienced Kac’s creative process firsthand, and said he enjoyed the challenge of working outside of his department and thinking up new ways to explain the processes taking place.

“There’s a certain energy and excitement in just thinking about things differently,” he said. “I think it helped me as a teacher.”

Continuing the Discussion

Following its exhibit at the Weisman, “Natural History of the Enigma” has since moved on to other showings, including recent exhibits in New York and Paris. Critical questions the work raises about life, technology and human intervention in biological processes have provided a unique platform to explore the broader, sometimes controversial, topic of genetic modification, the genetic engineering of plants and animals.

Kac and Olzewski participated in several panel discussions about the piece that explored how it was created, what it meant and some of the societal implications surrounding genetic engineering including ethical and moral implications, questions of intellectual property (which corporations hold over genetically modified foods) and food safety. The panel also asked the audience what they thought about genetically modified organisms being used for art.

Working with Diane Willow, an associate professor in the U’s Department of Art, Olszewski expanded the discussion to incoming university undergraduates. They included “Natural History of the Enigma” as part of a one-time fall 2009 freshman seminar on BioArt that examined the ways artists are accessing, critiquing and demystifying biotechnology. During the second week of the class, students explored the science behind Kac’s work, along with the ethical implications of creating art through genetic modification. The students went on to study other examples of Kac’s biological art and to create “bioportraits” — artwork that blended a self-portrait with elements from other living plants and animals.

Through an unlikely partnership, Kac and Olszewski explored new ways of thinking that blurred the lines separating their areas of expertise. The opportunity to collaborate on the same project allowed them to create a unique view into an often controversial subject and spur a conversation on what genetic modification means for society.

Images courtesy of Eduardo Kac