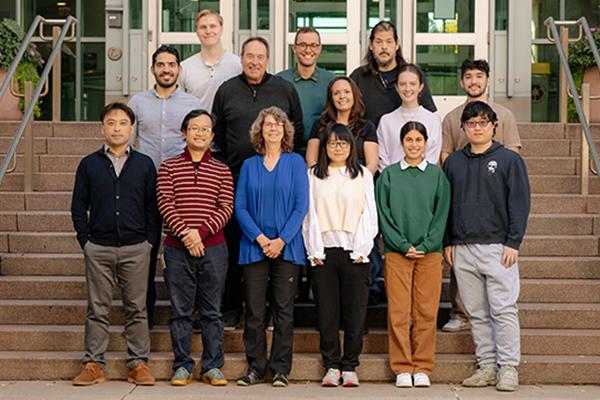

iBAM co-directors Laura Neidernhofer and Paul Robbins

Geroscience researcher Paul Robbins and his collaborator and partner Laura Niedernhofer thought they’d settled in Florida for good. They were researching aging at The Scripps Research Institute in Jupiter and living a block from the beach when Niedernhofer got a cold call from the University of Minnesota asking if she’d like to interview for the directorship of the Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism (iBAM), a part of the growing geroscience movement.

Growing Field of Geroscience

Geroscience, which believes that aging is the most significant risk factor for all chronic diseases and focusing on healthy aging rather than targeting individual diseases will have a more significant impact on health, is a burgeoning field.

Before transitioning to geroscience, Robbins started his career as a gene therapist, spending 22 years at the University of Pittsburgh, where he was a professor, ran a viral vector core facility, co-directed an institute of molecular medicine, and co-directed multiple large grants. As he came to the end of his time at Pittsburgh, he realized that all the different diseases he’d worked on, from cancer and muscular dystrophy to cystic fibrosis and osteoarthritis, stemmed from pathways that were also important for aging.

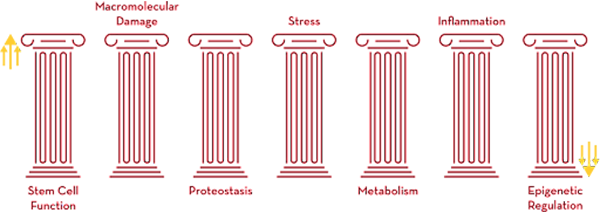

“There are many things that can go wrong with aging, called the hallmarks of aging. Research shows that all these hallmarks, such as chronic inflammation, stem cell exhaustion and cellular senescence, are linked and that treating one hallmark improved the others,” said Robbins. “This reinforces the general science hypothesis that targeting aging can have a dramatic effect on human health span.”

A State Priority

In the next five years, the number of people over 65 in the State of Minnesota will be more than the number of people between the ages of 0 and 18, which has never happened in the state’s history. That difference will continue to grow, and it’s imperative to figure out ways to keep people over 65 healthier and out of nursing homes and emergency rooms, which may not have the staff or funding to adequately treat a rapid influx of patients.

In 2015, the State of Minnesota, sitting on a budget surplus, asked the University of Minnesota for proposals for research areas worthy of funding. The State agreed to fund four Medical Discovery Teams, each focusing on a different area of crucial importance to Minnesotans, including aging. Due to the high demand for aging research, iBAM was promised $30 million over 10 years and bumped from discovery team to institute, and in 2018, Neidernhofer and Robbins said goodbye to the beach and took over leadership of iBAM.

University’s Diversity of Programs a Boon for Geroscience

“I think every university now has or is starting a program, center, institute, or department focused on aging,” said Robbins. “What makes Minnesota unique is the diversity of programs on campus.”

Since joining iBAM, Robbins and Neidernhofer have worked with bioengineers on developing technology to detect aging-related conditions. They’ve collaborated with researchers working on improving organ transplants. They have access to the renowned Masonic Cancer Center to determine how aging drives cancer and how cancer drives aging as well as neuroscientists doing important work on Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other types of dementia. iBAM also is working on ways to keep astronauts healthier after exposure to space radiation with the goal to obtain funding from NASA.

“Many researchers, in one way or another, work on aging. They might not think they do, but if you’re studying cancer, what’s the biggest risk factor? Aging. If you’re studying Alzheimer’s, what’s the biggest risk factor? Aging. You can go through a long list of these departments and their research programs and come to this same conclusion.”

15 Years of Collaboration

Robbins has always been interested in translational research—understanding enough about the basic biology of a disease to develop therapies for it—while Niedernhofer has a background working with mouse models that mimic conditions of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), a progeria syndrome that causes rapid aging in children. About 15 years ago, the pair combined their approaches to begin collaborating on the study of aging, using mouse models of accelerated aging for rapidly testing therapeutic interventions.

At this stage in their careers, Robbins focuses on developing drugs that target certain hallmarks of aging and Niedernhofer tests them in mouse models of accelerated aging. At iBAM, they run two different labs focused on their respective interests and this collaboration leads to tangible results. They are setting up clinical trials throughout the state to translate these treatments to people, with an emphasis on diversity to make sure their trials cover the full range of human experiences.

iBAM’s Biggest Breakthrough

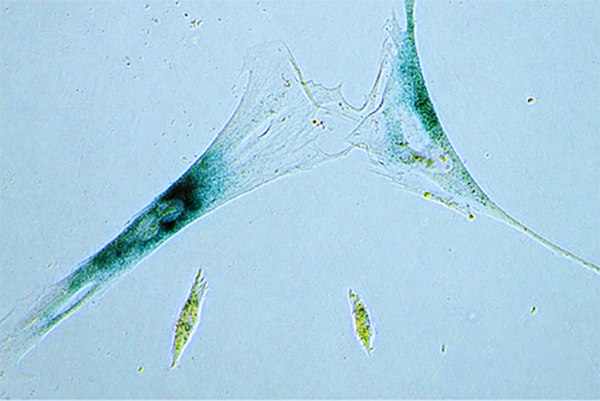

When cells are damaged, they undergo cellular senescence, a process that tells the cells to stop dividing and start releasing inflammatory factors that then tell the body to get rid of the cells. As humans age, they accumulate more and more senescent cells that release inflammatory factors, which leads to chronic inflammation that, among other things, can reduce stem cell function and impact metabolism.

Robbins and Niedernhofer hypothesized that they could develop drugs that specifically kill these senescent cells, termed senolytics. They began this process before arriving at iBAM, in collaboration with the Mayo Clinic, and have since identified the first drugs and even natural products that seem to target these senescent cells. There are currently more than two dozen trials around the world focused on the efficacy of these drugs.

If the clinical trials go well, this first round of identified drugs and natural products will be approved to clear these inflammatory cells. iBAM is currently working on getting a second generation of senolytic drugs into trials, with more to follow. One trial in particular is testing a natural product that is cheap and easy to procure and could seemingly be a gamechanger in protecting cells against senescence.

“The goal is to develop affordable therapies that not just rich white men in Silicon Valley can take. We want populations around the world to have access to these treatments,” Robbins said.

Minnesota-Based, Globally Minded

One of the first things Robbins and Niedernhofer did when they arrived in Minnesota was join the existing Alliance for Healthy Aging established by Mayo Clinic, which includes partners in England, the Netherlands, and Denmark with potential partners in Germany and Portugal. This collective meets every year to talk about joint clinical trials and cross-training opportunities. iBAM also started the Midwestern Aging Consortium as a way to build relationships among the schools between the East and West coasts that have programs, centers, or institutes working on aging.

“Aging is complicated. No one lab or institute is going to be able to do everything that’s needed in clinical trials. Every place has different strengths,” said Robbins. “iBAM has been a hub for some of these efforts in building out an international aging consortium.”