Estimates from the International Labor Organization (ILO) show that there are more than 4.9 million people trapped in forced sexual exploitation globally. The large majority of these people are women and children. To put this in perspective, there are 1 million more people experiencing sexual exploitation across the globe than the entire population of Los Angeles.

Human trafficking is a $150 billion industry, which presents unique challenges for anti-trafficking organizations. Design Against Trafficking, an initiative by University of Minnesota College of Design Northrop Professor Tasoulla Hadjiyanni, adds design as a tool in the fight against modern day slavery.

“Anything you do is not going to stop trafficking; this is a multi-billion dollar global industry that is never going to stop. It’s too huge,” says Hadjiyanni. However, her goal is to highlight the issue and amplify the work of anti-trafficking organizations that help survivors.

An Eye Opening Discovery

Eleven years ago, Hadjiyanni was asked by a colleague if she would be attending a talk on sex trafficking. At the time, she had little knowledge on the topic and carried the impression that sex trafficking only happened in far-away places. During the conversation, she found out that the average age of people experiencing sexual exploitation is 13. Her daughter was 13 at the time.

“When I realized that sex trafficking is happening right here in my city, in Minneapolis, I was just floored. I had this visceral reaction, and I thought, ‘I need to do something,’” said Hadjiyanni in a 2021 UMN interview for the OCSA (Outstanding Community Service Award) Faculty Award (watch). “Granted, coming from interior design, I didn’t know what I was going to do."

Utilizing Design to Fight Trafficking

Most of the stories that surface around sexual exploitation and sex trafficking are about survivors. Because Hadjiyanni came from a background in design, she brought a unique perspective to the conversation that has opened up a whole new area of study.

“I was coming from design, and all of our lives take place in places, in buildings, and I thought ‘Okay, here’s another lens to tell the same story,’” Hadjiyanni shared.

Out of this realization, the Placeness of Trafficking project was born. This was a research project that explored the types of places implicated in sex trafficking and the potential role design could play in preventing a place from being used for sexual exploitation. Findings from the project suggested that sex trafficking in Minnesota touched all kinds of places, from the obvious to the unexpected—hotels, bars, gas stations, highways, parks, schools, and private homes.

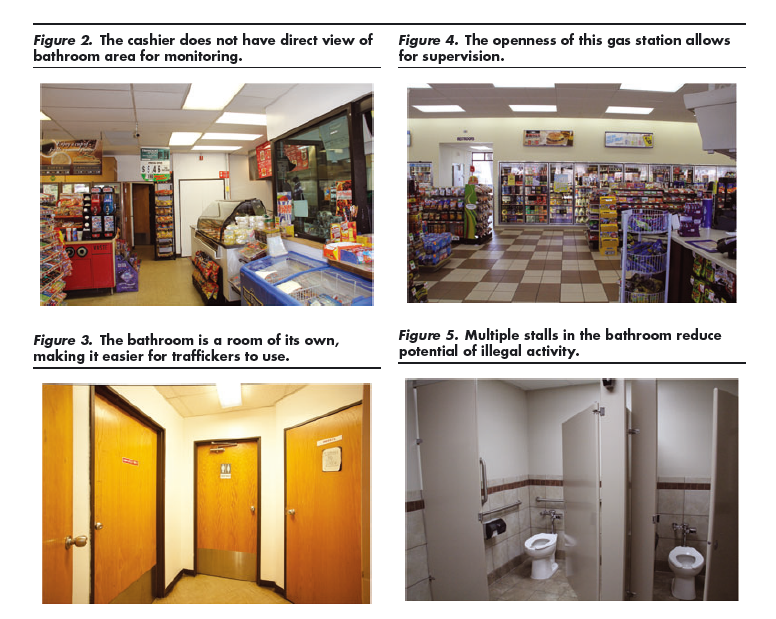

The project also identified design parameters as conducive to trafficking or not, including space planning and window placement. One example was the layout and design of a gas station bathroom: whether or not the cashier could see the restroom determined whether traffickers utilized it.

Currently, Hadjiyanni focuses much of her time on the project When Places Speak, which was an offshoot of the Placeness of Sex Trafficking paper. When Places Speak is a photography exhibit that provides a forum to raise awareness about the places associated with trafficking. The exhibit often includes photos of places where recruitment and exchange happens, places used by law enforcement to stop trafficking, and places for survivors to transition. The exhibit started with Minneapolis in 2016 at the Goldstein Museum of Design and now includes seven cities around the world, with multiple other locations in the pipeline for future exhibits.

By having these conversations around the places sex trafficking touches, whether obvious or not obvious, When Places Speak is shedding light on the fact that this is happening in our communities.

Impact to Date

Hadjiyanni’s work in design and trafficking has been difficult to numerically measure due to the nature of the work and the main goal being to raise awareness. However, there are a few anecdotes that have come out of the project.

As one can imagine, this initiative has opened a whole new conversation around the fight against sex trafficking and raised awareness across the country and globe. Design and trafficking was not an established area when Hadjiyanni began this line of inquiry. Due to her work and research, additional graduate students have devoted their thesis projects on healing environments for survivors which can be found on the website under Architecture. Other students at the University of San Carlos in Cebu City, Philippines, initiated their own When Places Speak exhibit, proving the widespread nature of Hadjiyanni’s work. Partnerships with Parsons School of Design in New York City, North Dakota State University, Frederick University (Cyprus), and the University of West Attica (Greece) continue to support that Hadjiyanni’s Design Against Trafficking is meeting the goal of raising awareness across the globe and activating higher education institutions and design programs.

Additional evidence for the widespread impact of the projects in Design Against Trafficking are the multiple anti-trafficking organizations that are now more aware of design as a tool in their fight against trafficking, from the Rotary Club of Community Action Against Human Trafficking to Minnesota-based The Link and Brittany’s Place as well as international organizations, such as the Office of the National Rapporteur on Human Trafficking and the National Center for Social Solidarity in Greece. It is also worth noting that the Design Against Trafficking website has had over 15,723 visitors since its launch in 2019 with over 109,190 visits.

The When Places Speak exhibits specifically have had a powerful and thought-provoking impact on audiences. One Minneapolis viewer found the exhibit to be "disturbingly brilliant," revealing the unsettling reality of trafficking, which is often a hidden issue. This realization has spurred a sense of urgency and introspection, with viewers questioning how such challenges might be present in their own communities and expressing a desire to take action to prevent further exploitation. Additionally, the exhibit has underscored the important role of student involvement in fostering local dialogue and enhancing community responsiveness, demonstrating how art can be a catalyst for social change.

Future Aspirations

Though Hadjiyanni has already expanded the When Places Speak exhibit globally, she says the work is not done yet. She is in the beginning stages of planning exhibits in the countries of Columbia and Ecuador, along with other cities in the United States.

Building these exhibits requires partnerships with institutions in the host cities. These partnerships often take several years to build as they require relationship building with faculty and anti-trafficking organizations, raising funds, identifying places to photograph, finding photographers and more. Funding is among the biggest barriers to advancing the exhibits, particularly on a global level.

“There is a lot of work that needs to be done, first of all with raising awareness,” says Hadjiyanni.

The long-term vision for Hadjiyanni is to spread this work across the globe and raise as much awareness about the prevalence of sex trafficking in all communities. To learn more about Design Against Trafficking’s initiatives and the many other projects that have come out of it, visit the website at designagainsttrafficking.com.