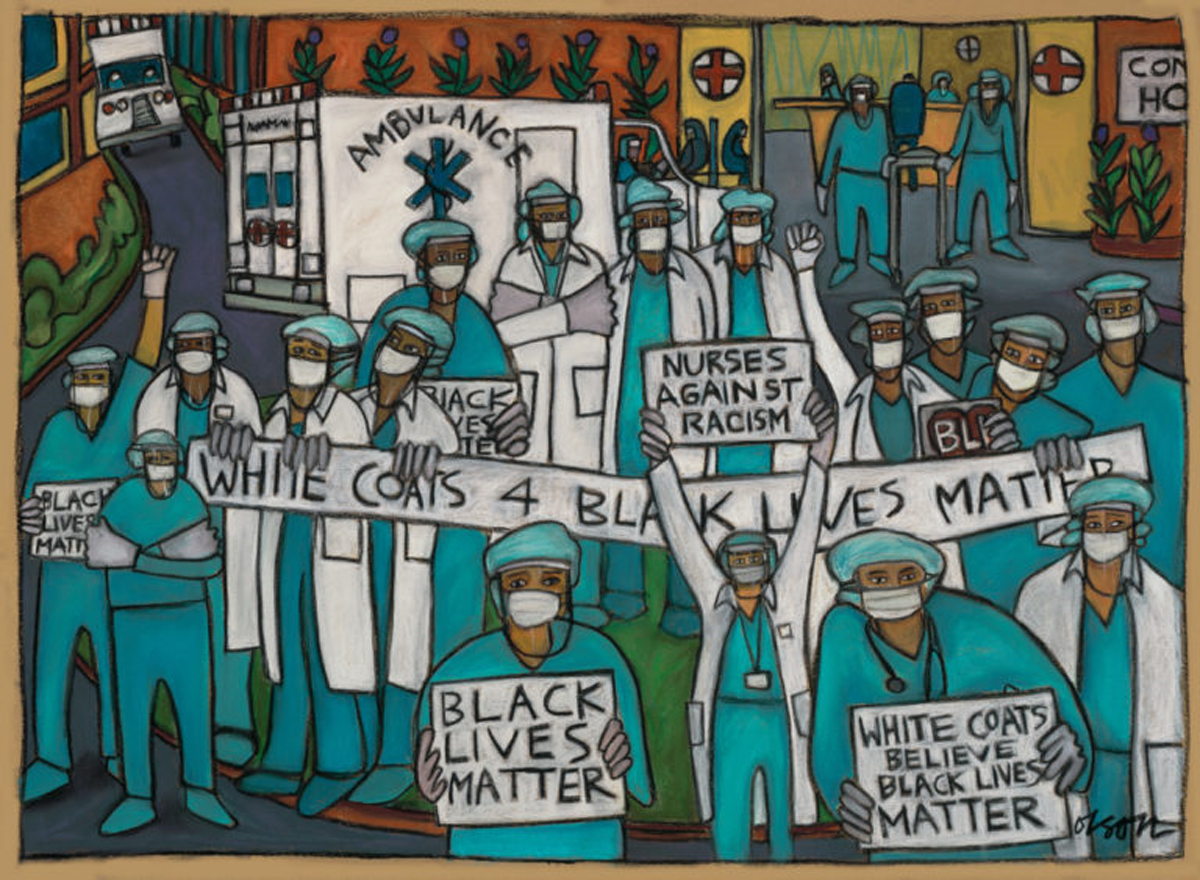

Note: the paintings throughout are by Carolyn Olson from her Essential Workers series.

Amid a traumatic, lonely, and polarizing pandemic landscape in rural Minnesota, Associate Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Devaleena Das created an open-access digital archive of experiential covid stories called SWaBS (Stories of Wisdom from Bodies in Separation: Archiving the Coronavirus Pandemic Through the Lens of Humanities) that captured stories of human resilience and hardship and narratives of grief and segregation to show the commonalities across differences in human bodies.

“At the onslaught of the global pandemic, I lost my 3-day-old infant followed by the intense tragedy of the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota,” said Das. “At global, national, local, and personal levels, it was a paralyzing and gloomy time, but it was also a moment to look inwardly and understand that this is an opportunity for communities to come together more intensely.”

Credit: Carolyn Olson

Covid-19 Provides a Prism for Marginalized Perspectives

In the largely rural Arrowhead Region of northeastern Minnesota, inequalities play out across all aspects of life, from high school graduations to the health care system. During the Covid-19 pandemic, both of the regional hospitals were overcrowded and rural healthcare workers experienced compassion fatigue and burnout. Additionally, due to shortage of resources and medical staff, the hospitals had to prioritize saving lives on the basis of survivability. The healthcare crisis was further aggravated by mistrust in the healthcare system among marginalized communities who have witnessed discrimination from generation to generation.

Credit: Carolyn Olson

Add to that the stress of unstable and uncertain economic times, with many individuals experiencing furlough and unexpected workplace closures, resulting in situations where people were unable to communicate their sorrows and grief. Finally, the barrage of misinformation, or infodemic, led to xenophobia and conspiracy theories, causing serious risks to health and well-being.

“Life under Covid-19 provided a prism, magnifying marginalized perspectives. There was a vacuum for humanitarian understanding, for compassion, and for love,” said Das. “I strongly believe that one reason for social injustices, pandemics, environmental racism, and climate catastrophe is rooted in the hierarchy of human bodies.”

Using Tools of Humanities to Counter the Infodemic, Isolation, and Polarization

Das envisioned a program that would combat this vacuum and identify problems of discrimination in healthcare while countering the infodemic and providing economic support to furloughed individuals. She hired and trained furloughed individuals in oral history collection. These individuals then collected 110 stories from the Duluth community, prioritizing diversity in religion, sexuality, race, and economic backgrounds and interviewing a range of people from recent high school graduates and senior citizens to recent immigrants and long-term residents. The range also included people who believed that Covid-19 was a political hoax, those recovering from the disease, and anti-vaccination and anti-mask individuals.

Since transcripts alone would be uninteresting for mass consumption and very technical terms can be alienating to non-academic community members, Das requested these stories be told using the tools of humanities, such as storytelling, visual and creative art, music, photography, films, and podcasts. These tools activated empathy, compassion, and critical thinking to help people better understand histories of health inequities and how the individual’s position in the healthcare system is conditioned by privileges and patriarchal power.

Credit: Carolyn Olson

“These are very simple tools of communication, often untied to any particular language, that touch the human heart and appeal for compassionate social change,” said Das. “The power of humanity is storytelling and these tools of humanities can change an entire generation.”

One storyteller, Elizabeth Spehar, looked at the complicated mind-body relationship in a multi-genre project called Integration: Hopes for an Interabled Future. Spehar had relied on cycling as a saving grace during quarantine, but a broken foot suddenly took away that option, leading to her understanding that the likelihood of any person acquiring a disability temporarily or permanently is statistically very high. Interviewer Brooke Wright, who is visually challenged, brought in the voices of rural individuals with disabilities severely impacted by the pandemic.

Ultimately Das and her team created a collection capturing facets outside of the technical scope of biomedicine, statistics, charts, and numbers that are often beyond the understanding or interest of the community. This empowering collaborative work also strengthened relationships between the University and the surrounding communities.

Devaleena Das gives interview about SWaBS.

This collection was presented in an on-campus exhibition at the Tweed Museum of Art and a digital exhibition, which is open access and has been accessed over 2,200 times in FY 2021-22.

An Enduring Impact

“The best way to prevent pandemic misinformation was by weaving a garland of similarities in tragedy, grief, loss, and loneliness in the midst of many differences,” said Das. “SWaBS did that. These basic human emotions gathered in SWaBS brought the community together where we were able to juxtapose people with ideologies from diverse polarities.”

SWaBS recorded diverse stories for posterity, warding against selective and revisionist history and creating space for the unheard. For researchers, including epidemiologists and policy makers, these stories provide a way to see beyond lab results and vital signs as there is a growing understanding that pandemic experiences cannot be reduced to a set of quantifiable indicators. Some epidemiologists are using the SWaBS archive to inform their quantitative findings that can develop and translate into evidence-based policies.

“This oral history archival and research project is a way to raise awareness about the significance of human bodies and its enduring negligence in Western epistemology. As the project captures experiential stories from diverse bodies, the archive enables us to understand how black, brown, white, female, male, trans, queer, and disabled bodies, often capitalized to serve racial and sexual hierarchies of empires and nation-states, must be treated equally with dignity and respect to prevent global pandemics,” said Das.

Das is also talking to other researchers and scientists who are interested in using her work and the SWaBS model for their own research efforts. She is working on National Endowment for the Humanities and National Institutes of Health grant applications that tie in members of the World Health Organization in supporting and expanding SWaBS to incorporate maternity health of women of color and Indigenous trangender community's challenges, especially in global south countries such as Pakistan, during pandemics. She is also in conversation with the Center for Disease Control about adding SWaBS to the CDC History Collection.

About the Researcher

Das holds a PhD in Australian Feminist and Aboriginal Studies from the University of Calcutta, during which time she conducted field research for her thesis on cross-racial interactions on women’s health and bodily challenges between settler and Indigenous women in Australia. She completed post-doctoral work on body studies and biopolitics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current research interest lies in initiating ethical and respectful understandings of marginalized human bodies to move discourse beyond Euroamerican thought. She holds dual appointments in the Department of Studies in Justice, Culture and Social Change at University of Minnesota Duluth and in Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health in the School of Medicine.