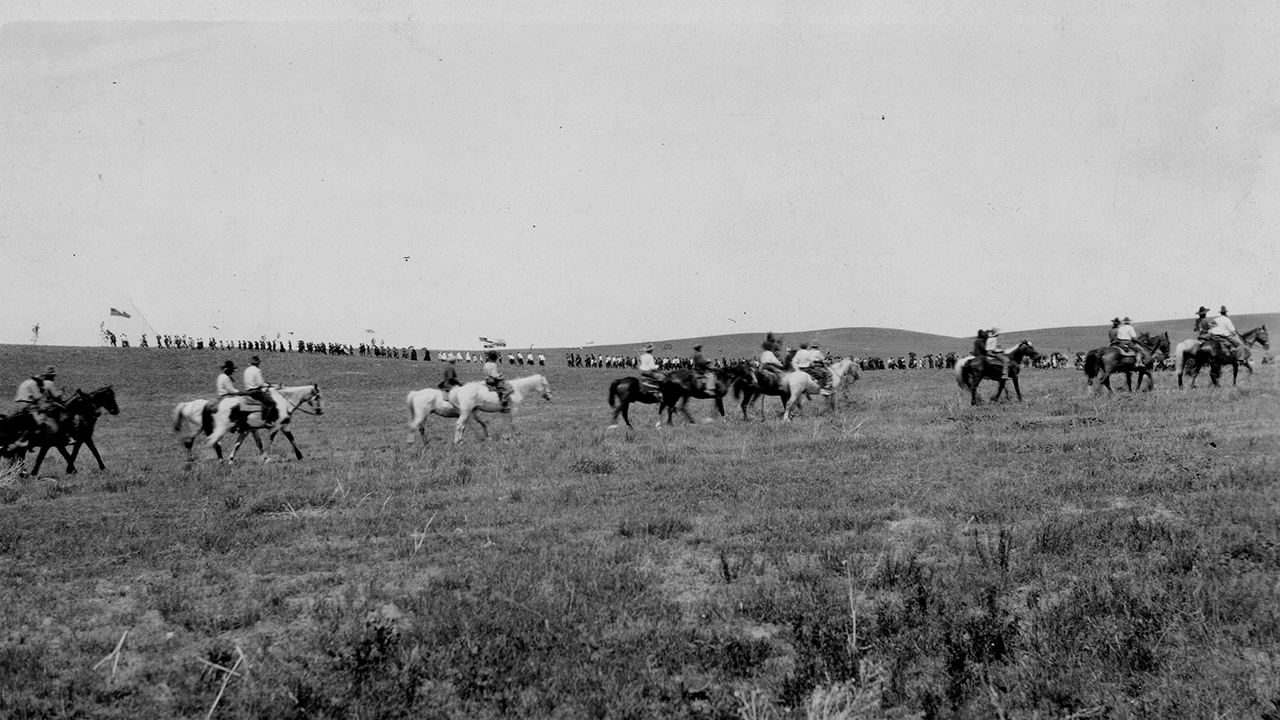

“Procession on Horseback at Catholic Sioux Congress, 1923,” which appears in Translated Nation, shows an example of how Lakota/Dakota people reconnected their communities and territories/homelands while also engaging with colonial institutions like the Catholic Church. Source: Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries.

Growing up, Christopher Pexa heard stories from his relatives and elders at Spirit Lake, a tribal nation of Dakota people in North Dakota. These spoken histories were a way to keep the traditions and values of the Dakota people alive for future generations.

Inspired by that concept, Pexa, Ph.D., now an assistant professor of English and of American Indian Studies in the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts, dedicated his research to exploring the important role that oral and written histories have played in preserving the culture of the Dakota. His book, Translated Nation: Rewriting the Dakota Oyate, scheduled to be released in June by the University of Minnesota Press, reveals how, in the face of pressure to adopt the culture of European settlers, the Dakota people found subtle ways to weave their traditions, ethics, and values into cultural frameworks imposed by the settler state.

Pressure to adopt settlers’ ideals and religion stretch back as far as the 1830s, Pexa said, with missionaries’ efforts to convert American Indians to Christianity. Then, the creation of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879 along with the introduction of federal policies related to agriculture, property, and education ushered in the “assimilation era,” a more formal and wide-reaching effort to overwrite traditional native practices and values with those of settlers. For example, while American Indians believed a responsibility for and to home territories belonged to the whole community, settlers placed an emphasis on property and individual land ownership.

While the assimilation era affected American Indians across the country, Translated Nation focuses on the Dakota, taking a chronological look at written and oral histories starting around the 1862 US-Dakota War and ending with present day oral histories. The book, which started as a dissertation for Pexa’s doctorate degree in English at Vanderbilt University, originally focused exclusively on oral histories. He drew from an archive of videos available at the Spirit Lake Nation that were recorded in the 1990s as part of a Dakota language teaching program.

Listening to these oral histories, he said, gave him a frame of understanding for how to think about the written histories that he would later research in writing the book.

“Engaging with those, listening to those, watching those; that really led me to the other, more literary texts and materials,” he said. “I was hearing a lot of resonances in the understanding of community, of tribal nationhood and peoplehood, and tribal ethics. They sort of taught me how to think about and read these authors.”

Cultural Camouflage

Drawing from assimilation-era Dakota authors, such as Nicholas Black Elk, Charles Eastman, and Ella Cara Deloria, as well as written records from settler missionaries, Pexa’s research focuses on the concept of “translation”—the act of learning to interpret something within and across not only languages, but cultural and philosophical understandings.

The lens of translation helps to reveal how the Dakota came to embrace a “doubleness” in their identities that allowed them to preserve important traditions and values even as they assimilated. For example, many Dakota came to embody aspects of the Christianized, converted identity stressed by settler missionaries, while at the same time following the Dakota tradition of thinking and talking about nonhuman entities (like lightning) as powerful beings.

Pexa describes this doubleness as a sort of “cultural camouflage,” where the Dakota kept important aspects of their peoplehood alive not by overtly resisting the pressures of assimilation, but through subterfuge—threading in elements of their traditions and values in ways that often flew under the radar to a non-Dakota audience. For example, Pexa found that in reading Eastman, who in some ways appeared to be an advocate for assimilation, he discovered allusions to the concept of Dakota kinship—the people’s strong commitment to territory and the relatives and communities that inhabited that territory.

“Eastman is citing what’s always been there, these traditions,” Pexa explained. “He’s keeping them alive. He’s making them new again for future generations.”

As Translated Nation’s release date approaches, Pexa said he hopes his work will help portray enduring aspects of the Dakota people for the newer generations and show how these elements of culture have resurged and renewed traditional Dakota values over time.

“It’s a terrific relief to see the book come together and exciting to be able to finally share it with a broader audience,” he said. “One hope that I have is that this moves local Dakota history, philosophy, and politics beyond the container of ‘tribal history’ and makes people think about language, people, and place in more decolonized ways.”