Every story is a brain story, and these stories are being increasingly illuminated by emerging portable magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies. Though they are new to the scene, these small and highly portable MRI systems offer exciting and important opportunities for researchers to conduct neuroimaging research in remote and underserved communities, filling significant gaps in scientific knowledge.

With this new technology, however, comes new ethical considerations and the need for revised protocols, which is one of the things researchers at the Consortium on Law and Values in Health, Environment & the Life Sciences are working on as part of a four-year project sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health’s BRAIN Initiative. This project is the third in a trajectory of grants led by Susan Wolf, the Consortium Chair and an expert on emerging technologies, and Francis Shen, the Consortium’s co-chair as well as one of the nation’s top thinkers about the ethical, legal, and societal issues raised by new neuroscience methods and neuroimaging.

“This trajectory of grants originated in the University of Minnesota’s Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, a hotbed for innovation in neurotechnology and neuroimaging,” said Shen. It was there that researcher Michael Garwood began to develop one of the first highly portable MRI systems in the world.

Portable MRI can empower new researchers and even community groups to conduct neuroimaging research, but Wolf points out that this raises challenging questions of how to ensure safety and appropriate protections for research participants. In addition to the portable MRI technologies being developed by research institutions in controlled, regulated environments, there are also efforts to create open source MRI, meaning, in theory, that anyone could use an instruction manual to put together an MRI system.

“We’re rapidly entering a world in which there will be much greater access to portable and accessible MRI through a variety of different technologies. But what they share in common is that they open up the possibility for new types of research,” said Shen.

MRI research has historically required the participant to come to the scanner, but now the scanner is starting to go to the participant. On the one hand, this is a very exciting prospect for researchers as it gives them the opportunity to improve inclusion in research, according to Consortium Chair Susan Wolf.

“Research has suffered from a lack of inclusion and a lack of having the kind of diverse participants we need in order to understand not just the neurological functioning of people who are able to come to a big hospital center in an urban setting, but more broadly the functioning of people across the United States and across the world,” said Wolf. “The ability to go into a remote field setting that could be hundreds of miles from a major hospital allows researchers to gain needed knowledge and build the kind of robust, representative databases that are essential to making progress in understanding the brain.”

On the flip side, introducing this technology to populations that are potentially in an underserved setting without easy access to healthcare and healthcare coverage raises questions. For example, how should a researcher handle discovering an incidental finding, such as a mass or a tumor or other brain pathology?

Another consideration is building appropriate capacity and oversight for new researchers that may now gain access to portable MRI technology. How, for example, can a community college or a psychology professor in a small college without a history of institutional review boards or the oversight of a safety committee conduct MRI research ethically and safely?

Yet a third consideration (among many more) is ensuring privacy for the participants. Portable MRI machines could be set up anywhere. A person could be getting a brain scan while crowds of people pass by and that data could be transmitted to the cloud. How do researchers guarantee privacy for these individuals and their data?

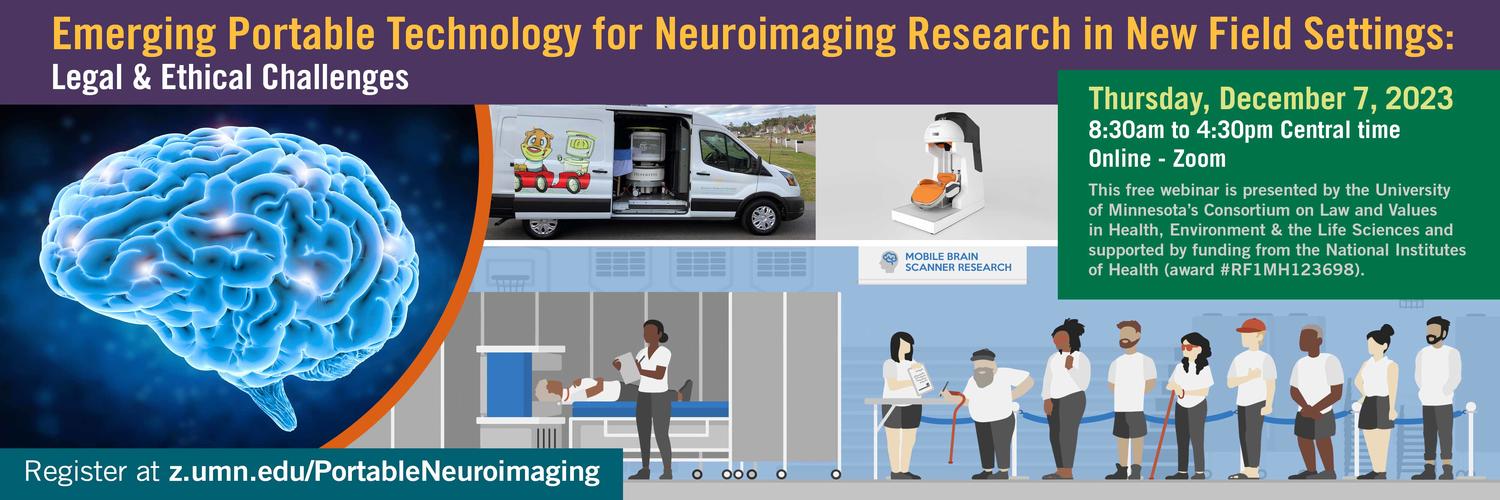

As leaders of a national working group of neuroethics, neurolaw, and neuroscience experts, Shen and Wolf are at the forefront of a project with the ultimate goal of developing evidence-based recommendations for the ethical conduct of research using portable MRI. After a four-year process researching these thorny issues, the working group put together 15 recommendations that will be published in the Journal of the Law and the Biosciences, and in a forthcoming symposium in the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics along with a checklist to aid researchers using portable MRI. The Consortium also held a conference in December 2023, and these recordings are available to the public online.

“The working group sees great value and potential in these tools. Sometimes I think that ethics of research gets viewed as the ethics police, like we’re trying to stop something,” said Shen. “But if we don’t attend to these ethical and legal issues, the technology won’t produce the benefits it potentially could. We’re trying to create guardrails that can help scientists achieve the full potential of portable MRI.”

The Consortium on Law and Values has been a homebase for grant-funded work on the ethical, legal, and societal implications of emerging biomedical technology for years and is home to a number of grants on research ethics and a range of technologies. The Consortium has a long history of consulting and collaborating with University of Minnesota researchers and those at other institutions on multi-institutional grant proposals. As a confederation of centers, the Consortium’s work crosses most of the University, with 21 member centers dealing with the societal implications of biomedicine and the life sciences.