UMN Gordon W. Gullion Endowed Chair in Forest Wildlife Research and Education and lead for the Voyageurs Wolf Project Joseph Bump has always worked with large mammals, particularly carnivores and their prey, and is motivated by understanding the role that animals play in a system. When it comes to wolves, he’s also intrigued by the love-hate relationship humanity has with wolves. They were once completely eradicated from all the lower 48 states, except Minnesota, and now as the wolf population is being restored, they’re facing pushback from some community members.

“If wolves cause conflict and some people hate wolves, how can we use science to help improve humanity’s relationship with wolves through better management?” Bump asks. “Beyond that, how do we effectively communicate wolf ecology with a broad audience?”

Enter the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) Residential Fellowship program, which supports and encourages interdisciplinary intellectual discourse and community. Bump was accepted into the fellowship program with a two-pronged plan: develop a series of interactive graphic art posters that communicate essential aspects of wolf biology and develop methods to make prints of wolf specimens to creatively frame their natural history, causes of mortality, and invite viewers to examine their relationship with wolves.

“My research group started by thinking about scientific posters, which have a very traditional format: maybe three columns with a title bar and they move through the structure of a traditional scientific paper,” said Bump. “We wanted to break away from that and brainstormed about different ways to graphically represent some of the same information in a way that would better draw viewers in creatively.”

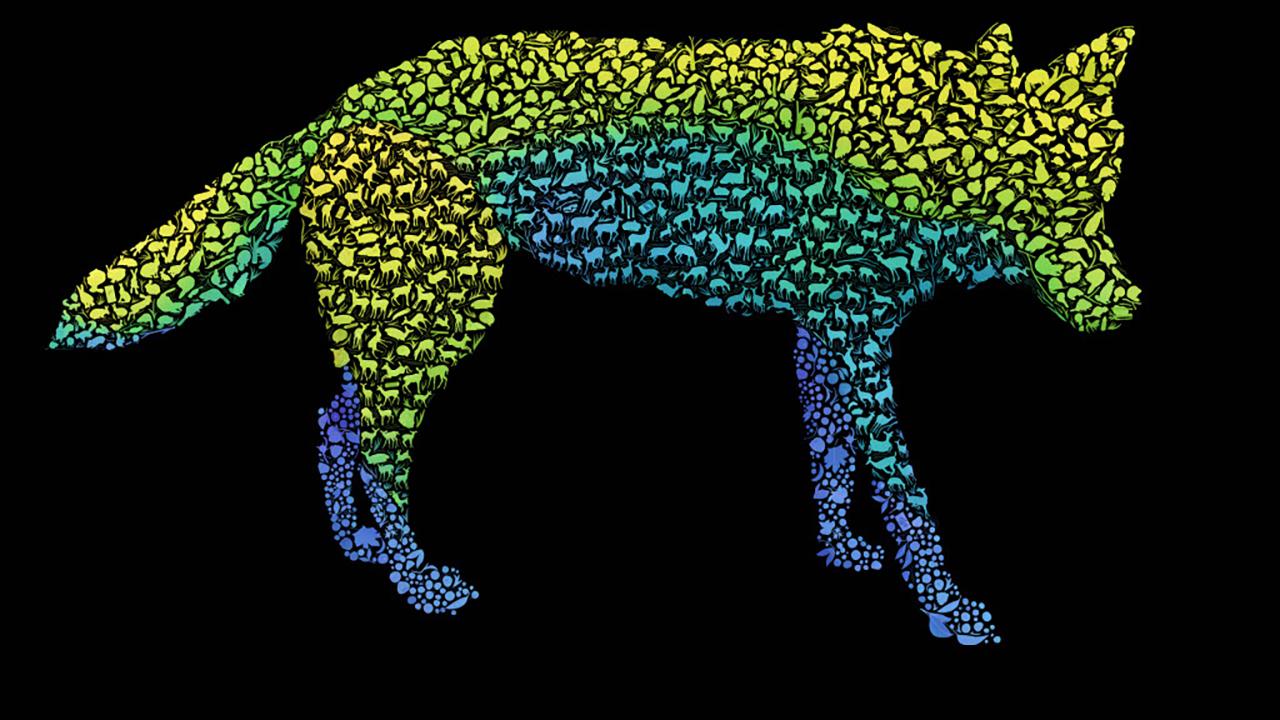

The result: a poster of a wolf made up of composite diet items. From a distance, the viewer sees a mosaic of a wolf but upon closer inspection the pieces represent diet items in direct proportion to what’s documented in the data. Bump would love to see these posters used in lesson plans for middle and high school students, as well as expand the concept to other carnivores.

The idea of making prints directly from wolves dates back to Bump’s college years when he spent summers as a commercial salmon fisherman on Kodiak Island, Alaska and was introduced to fish printing. Fish printing comes from the Japanese Gyotaku tradition of spreading natural ink over fish then applying rice paper on top of the ink to serve as a record of having caught the fish.

This practice evolved to become a highly refined artform, and Bump envisions it as an inspiration to make prints of wolf specimens that are recovered for research after they’ve died in the wild. These prints can then be a respectful way to showcase and educate about the natural history of wolves, including the causes and frequency of mortality, and hopefully help build empathy for how hard life can be for a wolf. Most wolves die young and starvation or being killed by neighboring wolves is common.

“The hope is that a series of wolf prints depicting different causes of mortality are produced to form a collection that can be displayed as fine art in a gallery or as science communication in a museum exhibit where they’re accompanied by natural history explanations. The goal is the artistic print draws someone in and, with the additional natural history information, viewers can hopefully leave with a better understanding of wolf ecology.”

Bump has a lot of good things to say about the IAS fellowship, which creates the space for transdisciplinary conversations and provides a forum for faculty members to develop ideas and challenge perspectives to spawn new research directions and collaborations.

“As an IAS Fellow I’m not just surrounded by scholars in ecology and conservation. I’m surrounded by a community that are experts in different fields,” said Bump. “This community is great at talking out ideas and offering constructive feedback. These fellowships are an incredible opportunity and a real asset to the UMN research community.”