There’s more to talking about science than just conveying facts. Skilled science communicators can tell memorable stories, form connections with people, and create a contagious sense of enthusiasm around their field of study.

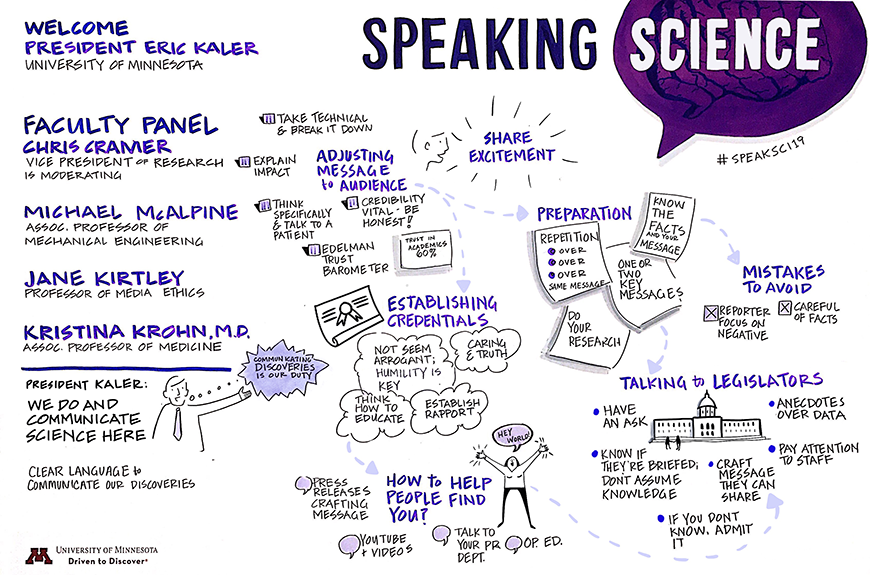

On January 17, the University of Minnesota hosted a conference to help scientists more effectively share their knowledge and research with the audiences outside of academia. Speaking Science: Communicating with Media, Funders, Policymakers, and the Public brought faculty, post-doctoral researchers, and graduate students together from across disciplines to hone their communication and storytelling skills.

The one-day event, hosted by a collection of colleges and units from across the U of M Twin Cities, featured interactive training exercises, break-out sessions, and a keynote presentation by Emily Graslie, chief curiosity correspondent at Chicago’s Field Museum and creator and host of YouTube science channel “The Brain Scoop.”

For those who couldn’t make it to the event or would like a recap, here are eight takeaways.

1. Make—and Remake—Your Point

Think about the one or two main points you want your audience to remember after the conversation. Make sure to hit these early on in your discussion—and a little while later, repeat them.

Repeating your main points increases the odds that they will end up in newspaper, radio, or television coverage and stick in your audiences’ minds. If you have a presentation, use the last slide to touch on your main takeaways one final time, rather than asking for questions.

2. Impart the Impact

How is your research going to affect people? Could it help your neighbor, students, or patients? Might it change how people think about the world around them?

Focus on conveying the potential impact of your work. It’s not about dumbing down your research, but making it real to your audiences and giving it a human touch. Consider how simple visuals could help demonstrate the concept you’re explaining.

3. All About Audiences

It’s tempting to concentrate on sounding smart when speaking about your work. Instead, focus on how you can best educate the audience you’re speaking to.

Talk the way you would to a friend, relative, or patient—in simple but precise words. Think about the tone and language that might resonate with your audience. Maintain a sense of humility to avoid appearing to talk down to them. If speaking to a reporter, feel free to ask what their background is and offer to explain concepts before the interview starts.

4. Keep It General

Whether it’s an on-camera interview or a public speaking event, time is limited and interruptions are always possible. Prioritize the time you have by focusing the discussion on the main points and the broader picture, rather than delving into details.

For practice, look for the “big picture” in someone else’s work, noticing the details you skip over along the way. What does the equivalent look like in your own research?

5. Tell Them a Story

Anecdotes, not data, are what tend to leave a lasting impression. Go beyond the statistics to find a compelling human interest angle that helps the subject become real and relatable to your audience.

It will help to let your passion come through. Why did you dedicate yourself to this work? What excites you about it? What do you tell your spouse, friend, or family member at the end of the day?

6. Trust Is a Must

A key part of communication is demonstrating that your expertise and input is trustworthy. While audiences will respect your title and position from the start, their trust may be harder to win.

Establish a rapport early on by being authentic and speaking as clearly and concisely as you can. Be transparent about what you do and don’t know—it will help to maintain your credibility.

7. Connections in Controversy

When it comes to contentious subjects, move beyond the agree/disagree divide to find intersections between what you care about and what your audience cares about. It may help to spend some time thinking about where the opposition is coming from.

Remember that “fact battles” rarely solve anything—throwing more data at people who disagree won’t necessarily change their minds or their behaviors. Strive for deeper levels of conversation.

8. Plan to Pitch

When your research applies to current events, it’s a good time to alert reporters that you have something to add to the conversation. Reach out and show how your expertise plugs into the larger issue, keeping the connection specific and straightforward.

Public relations staff in your department may be able to help you create press releases, connect with reporters, or pitch opinion pieces to the local paper—all with the exact message you want to convey.

Thank you to the following conference speakers, whose talks were the source of the tips in this post:

- Jane Kirtley, JD, Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, College of Liberal Arts (Twin Cities), U of M

- Kristina Krohn, MD, Medical School, U of M

- Michael McAlpine, Ph.D., Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Science and Engineering, U of M

- Elisia Cohen, Ph.D., Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, CLA (Twin Cities), U of M

- Timothy Blotz, KMSP-TV News

- Michelle Cortez, Bloomberg News

- Emily Graslie, Field Museum and The Brain Scoop

- Mary Milla, communications coach

- Amanda Stanley, Ph.D., COMPASS

Watch a recording of the morning speakers or see a collection of tips from last year’s conference.